Introduction

In software engineering, certain concepts like webhooks require careful architectural decisions before implementation. Webhooks, whether you want them or not, add another layer of complexity to your system, and you must handle them with care to ensure their reliability and value. That's why many businesses prefer using external services to handle webhook deliveries to their customers.

If you're a software engineer, understanding how webhooks work under the hood and building some of them can be a valuable exercise. In this article, we will explore how to build a webhook service using Golang for an imaginary payment gateway with an API as support.

When someone makes a request on the payment gateway to request a payment, we send a response, but we also contact the webhook service written in Golang to send a webhook request. We will use the Redis channel for communication between the Golang service and the API built with Flask. This channel will send data and instruct the Golang service to send a request (webhook) on the URL passed in the payload.

In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into technical concepts such as queuing, webhook, goroutines, and exponential backoff, providing examples and insights into building a robust Golang webhook server.

How to build a webhook service?

Before coding, we need to discuss our approach to build a webhook service. Let's start by understanding what are webhooks and how they work.

What are webhooks?

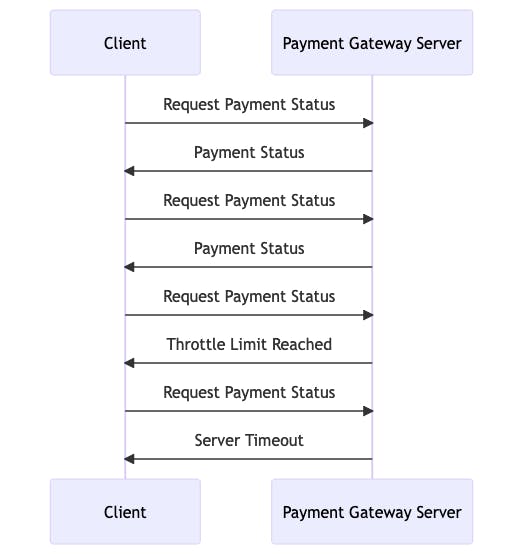

Webhooks are automated messages sent from one system to another triggered by specific events. They are used to notify other systems in real time when something happens, without the need for continuous polling. In a payment gateway situation, when you make a payment request, you can poll onto an endpoint with the id or the reference of the transaction to get the updated status. This method has its own drawbacks because you can be limited to the number of requests you can make (throttle), and there can be server timeout for example.

The diagram below illustrates the action of polling and scenarios that can happen such as throttle and server timeout:

Here is a description of the diagram above :

Client Requests Payment Status: The client repeatedly requests the payment status from the payment gateway server.

Server Responds with Payment Status: The server responds with the current payment status.

Throttle Limit Reached: After a certain number of requests, the server may throttle the client, limiting further requests.

Server Timeout: If the server is unable to respond within a certain time frame, it may result in a timeout error. Following the issues of throttling and server timeouts, businesses to be more reliable and fast combines allows their client to poll but also to receive webhooks. What happens is that, if a webhook is not received after a certain amount of time, the client can start polling to retrieve the status. This gives the client many ways to get updates on a payment but also helps the business stay more reliable, robust, and developer friendly.

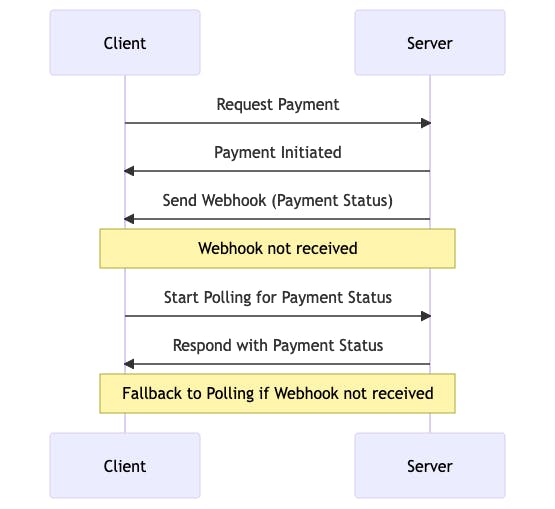

Here's a diagram that illustrates the process of using webhooks first, and then falling back to polling if the webhooks are not delivered:

Here is a description of the diagram above :

Client Requests Payment: The client initiates a payment request to the server.

Server Initiates Payment: The server acknowledges the payment initiation and begins processing.

Server Sends Webhook: The server attempts to send a webhook to the client with the payment status.

Webhook Not Received: If the webhook is not delivered to the client after a certain time, a note is made of this failure.

Client Starts Polling: The client, noticing the absence of the webhook, starts polling the server for the payment status.

Server Responds with Payment Status: The server responds to the polling request with the payment status.

Fallback to Polling: The entire process demonstrates a fallback mechanism where the client can resort to polling if the webhook is not received.

This approach ensures that the client has multiple ways to get updates on a payment, making the system more reliable, robust, and developer-friendly.

Most of the time, webhooks are HTTP POST requests made on a callback URL provided by the client. When a specified event occurs in System A, it triggers an HTTP POST request to a specific URL in System B. The request usually contains a payload with information about the event. System B's server then processes the request and takes appropriate action.

Now that we understand more about webhooks, let's discuss the challenges that come with designing a webhook service.

Difficulties of designing a Webhook service

Designing a webhook service is a complex task that requires careful consideration of various factors to ensure scalability, reliability, and security. Here's an in-depth look at some of the key challenges:

Scalability: Handling a large volume of requests is a common challenge in webhook services. The system must be designed to scale horizontally to accommodate the load, ensuring that it can process a high number of webhooks simultaneously without degradation in performance. Implementing concurrency is essential for managing multiple webhooks at the same time. This requires a robust concurrency model that can efficiently handle simultaneous requests.

Reliability: Managing a queue of webhook payloads is crucial to ensure that no data is lost and that each webhook is processed in a timely manner. Implementing a reliable queuing system helps in maintaining the order and integrity of the webhooks. However, webhooks can not be delivered sometimes. It happens. A robust retry mechanism must be in place to handle failed webhook deliveries. This often involves implementing exponential backoff strategies to ensure that the receiving system is not overwhelmed with repeated attempts in quick succession.

Security: Validating the payloads ensures that they meet the expected format and contain no malicious content. Implementing strict validation rules helps in preventing potential security risks. Encrypting the data transmitted through webhooks adds an extra layer of security, ensuring that sensitive information is protected during transmission.

Maintainability: Comprehensive logging is vital for tracking the behavior of the webhook service, aiding in debugging, and providing insights into the system's performance. Implementing detailed logging strategies helps in monitoring the system and can be invaluable in identifying and resolving issues. For the simplicity of this article, we will focus on the scalability part and reliability of the application. Security is vast and this can be discussed in another article. However, you can check this article on how to add security to your webhooks.

Coming back to the application to develop, we will use Golang. But why? Let's discuss the pros and cons in our case and why it is a robust choice of technology here.

Why use Golang?

In the context of building a webhook service, Golang's strengths in concurrency, scalability, performance, and strong typing make it a robust choice. The most interesting feature of Golang that will help us are goroutines and queueing. Let's dive deeper into these features.

Goroutines: Golang concurrency on steroids

Goroutines can be likened to supercharged threads but much lighter. They allow functions to run concurrently with others, enabling efficient multitasking.

To better understand Golang, here is a simple analogy.

Imagine a large restaurant during peak dining hours. In a traditional threading model, you might have a few waiters (threads) responsible for taking orders, serving food, and handling payments. If the restaurant is packed, these waiters might become overwhelmed, leading to slow service and unhappy customers. Now, consider the goroutine model in this restaurant scenario.

Instead of having a few waiters, you have a large team of nimble assistants (goroutines) who can quickly and concurrently handle multiple tasks. Each assistant is like a mini-waiter that can take an order, serve a dish, or process a payment. They can work simultaneously, efficiently utilizing the available space and resources in the restaurant.

These assistants are not only numerous but also lightweight, meaning they can quickly switch between tasks without much overhead. If one assistant is momentarily stuck or waiting for the chef, another can take over, ensuring that the service continues smoothly.

The restaurant manager (Golang's runtime scheduler) oversees these assistants, ensuring that they are distributed effectively across the available tables (CPU cores) and that they collaborate without getting in each other's way. In this analogy, the restaurant represents the computer's resources, the dining tasks represent the functions to be executed, the traditional waiters represent threads, and the nimble assistants represent goroutines. The ability to have many of these "assistants" working concurrently allows for highly efficient and scalable service, making goroutines a powerful feature in Golang's concurrency model.

Here's why goroutines are advantageous:

Lightweight: Goroutines are far lighter than traditional threads, consuming only a few kilobytes of stack space. This allows you to spawn thousands or even millions of them simultaneously without exhausting system resources.

Simple Syntax: Starting a goroutine is as simple as adding the

gokeyword before a function call. For example,go myFunction()will runmyFunctionas a goroutine.Efficient Scheduling: Golang's runtime takes care of scheduling goroutines on the available CPU cores, ensuring optimal utilization. A machine with 4 cores can run thousands of goroutines concurrently, thanks to the efficient scheduling algorithm. Here is a simple usage of goroutines in Golang

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ {

go printNumber(i)

}

}

func printNumber(number int) {

fmt.Println(number)

}

This code will spawn 10,000 goroutines to print numbers concurrently.

Queuing in Golang

Queuing is essential in managing the flow of data, especially in a webhook service that must handle a large volume of requests. Golang offers two primary ways of queuing:

Using Slices: You can implement a simple queue using slices, but this approach lacks concurrency control and can lead to race conditions.

Using Channels: Channels provide a way to communicate between goroutines and can act as a queue. They offer built-in synchronization, ensuring that data is safely passed between goroutines. To better understand channels, here is another restaurant analogy.

Imagine the restaurant's kitchen, where orders are prepared. In a traditional system without queuing, waiters might hand orders directly to the chefs, leading to chaos during busy times. If too many orders come in at once, chefs can become overwhelmed, leading to delays and mistakes.

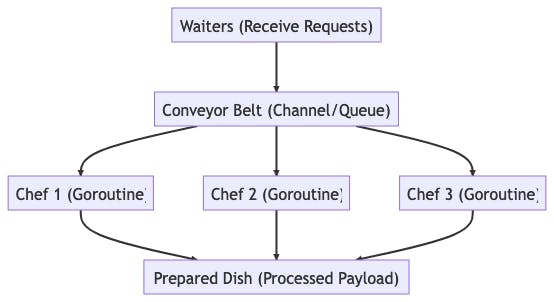

Now, let's introduce a queuing system using channels, akin to Golang's approach. In this model, the restaurant has a well-organized order queue, represented by a conveyor belt (channel). When waiters take orders from customers, they place them on the conveyor belt, which moves the orders to the chefs in a systematic and orderly fashion.

The conveyor belt ensures that orders are processed in the order they were received (FIFO - First In, First Out). Chefs can take one order at a time from the conveyor belt, prepare the dish, and then take the next order. If the kitchen is busy, new orders simply line up on the conveyor belt, waiting for their turn. This queuing system allows the restaurant to handle a large volume of orders without overwhelming the chefs.

It also provides flexibility. If the restaurant gets exceptionally busy, they can add more chefs (goroutines) to work on the orders from the conveyor belt. If it's a slow night, they can have fewer chefs, and the conveyor belt will still ensure that orders are handled in an orderly manner.

In Golang, channels act like this conveyor belt, providing a way to send and receive values between goroutines in a safe and organized manner. They allow you to create a pipeline where data (orders) can be processed concurrently (by multiple chefs) without conflicts or confusion.

Here's a diagram representing the restaurant analogy for queuing with channels in Golang:

In this article, we will go with channels as we need goroutines to communicate. Now that we understand better webhooks and the architecture behind the solution developed in this article, let's build our webhook service.

Project setup

To make things easier and simple we will use Docker for this project. We will have three services:

Redis: that will run the Redis image used to share data between the Flask API service and the Webhook Golang service.

api: This is the name of the service written in Flask. We will just expose a GET endpoint that will generate a random payload, send the payload to the Webhook service through Redis, and also return the generated payload. No need to implement a complex endpoint as the focus of this article is on the Go service.

webhook: the name of the service written in Golang. We will build an application that listens to data coming from a Redis channel and then process the payload and send it to the URL passed in the payload. As we are dealing with HTTP requests and we understand that other services can be unavailable, we will implement a retry mechanism (exponential backoff) and make it robust using Golang queues. The setup will take some time so I will advise just to clone the base of the project using this command :

git clone --branch base https://github.com/koladev32/golang-wehook.git

This will clone the base branch of the project that already comes with a working Flask project and docker-compose.yaml file.

Let's quickly explore the code of the Flask service written in Python:

from datetime import datetime

import json

import os

import random

import uuid

from flask import Flask

import redis

def get_payment():

return {

'url': os.getenv("WEBHOOK_ADDRESS", ""),

'webhookId': uuid.uuid4().hex,

'data': {

'id': uuid.uuid4().hex,

'payment': f"PY-{''.join((random.choice('abcdxyzpqr').capitalize() for i in range(5)))}",

'event': random.choice(["accepted", "completed", "canceled"]),

'created': datetime.now().strftime("%d/%m/%Y, %H:%M:%S"),

}

}

redis_address = os.getenv("REDIS_ADDRESS", "")

host, port = redis_address.split(":")

port = int(port)

# Create a connection to the Redis server

redis_connection = redis.StrictRedis(host=host, port=port)

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/payment')

def payment():

webhook_payload_json = json.dumps(get_payment())

# Publish the JSON string to the "payments" channel in Redis

redis_connection.publish('payments', webhook_payload_json)

return webhook_payload_json

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=8000)

First, we are creating a function that will generate a random payload called get_payment. This function will return a random payload with the following structure:

{

"url": "http://example.com/webhook",

"webhookId": "52d2fc2c7f25454c8d6f471a22bdfea9",

"data": {

"id": "97caab9b6f924f13a94b23a960b2fff2",

"payment": "PY-QZPCQ",

"event": "accepted",

"date": "13/08/2023, 00:03:46"

}

}

After that, we initialize the connection to the Redis using the REDIS_ADDRESS environment variable.

...

redis_address = os.getenv("REDIS_ADDRESS", "")

host, port = redis_address.split(":")

port = int(port)

# Create a connection to the Redis server

redis_connection = redis.StrictRedis(host=host, port=port)

...

The redis_address is split because the REDIS_ADDRESS will normally look like this localhost:6379 or redis:6379 (if we are using Redis containers). After that, we have the route handler function payment that sends a random payload webhook_payload_json formatted with the json.dumps method, through the Redis channel called payments, and then return the random payload.

This is a simple implementation of a Payment API gateway or just to put it simply a Mock. Now that we understand the base of the project, let's quickly discuss the architecture of the solution, and the implementation of some concepts to make it robust. We will discuss their drawbacks at the end of the article.

The architecture of the solution

The architecture of the solution is quite simple:

We have an API that acts as a Payment Gateway. A request on the endpoint of this API will return a payload but this payload is also sent through a Redis channel called

payments. Thus all services listening to this channel will receive the data sent.We then have the webhook service written in Golang. This service listens to the

paymentsRedis channel. If data is received, the payload is formatted to be sent to the URL indicated on the payload. If the request fails due to timeout or any other errors, there is a retry mechanism using Golang channel queuing and exponential backoff to retry the request.

Let's write the Golang service.

Writing the Golang service

We will write the logic of the webhook service using Golang in the webhook directory. Here is the structure we will attain at the end of this section.

webhook

├── Dockerfile # Defines the Docker container for the project

├── go.mod # Module dependencies file for the Go project

├── go.sum # Contains the expected cryptographic checksums of the content of specific module versions

├── main.go # Main entry point for the application

├── queue

│ └── worker.go # Contains the logic for queuing and processing tasks

├── redis

│ └── redis.go # Handles the connection and interaction with Redis

├── sender

└── webhook.go # Responsible for sending the webhook requests

Let's start by creating the Go project.

go mod init .

To create a go project, you can use the

go mod init name-of-the-project. In our case, adding the dot.at the end of the command tells Go to use the name of the directory as the name of the module.

Once the module is created, let's install the required dependencies such as redis.

go get github.com/go-redis/redis/v8

Great! We can start coding now. 😈

Adding webhook sending logic

Starting a bit unconventionally, we'll first write the webhook sending logic. Since we're using Golang queuing, and to streamline the development process, we'll begin by adding the system's first dependency: the function to send the webhook.

Create a directory called sender with the mkdir sender command. Then inside this directory, create a new file called webhook.go.

mkdir sender && cd sender

touch webhook.go

Inside the newly created file, let's add the required naming and imports and structs.

package sender

import (

"bytes"

"encoding/json"

"errors"

"io"

"log"

"net/http"

)

// Payload represents the structure of the data expected to be sent as a webhook

type Payload struct {

Event string

Date string

Id string

Payment string

}

Next, let's create a function SendWebhook that will send a JSON POST request to an URL.

// SendWebhook sends a JSON POST request to the specified URL and updates the event status in the database

func SendWebhook(data interface{}, url string, webhookId string) error {

// Marshal the data into JSON

jsonBytes, err := json.Marshal(data)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Prepare the webhook request

req, err := http.NewRequest("POST", url, bytes.NewBuffer(jsonBytes))

if err != nil {

return err

}

req.Header.Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

// Send the webhook request

client := &http.Client{}

resp, err := client.Do(req)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer func(Body io.ReadCloser) {

if err := Body.Close(); err != nil {

log.Println("Error closing response body:", err)

}

}(resp.Body)

// Determine the status based on the response code

status := "failed"

if resp.StatusCode == http.StatusOK {

status = "delivered"

}

log.Println(status)

if status == "failed" {

return errors.New(status)

}

return nil

}

Let's explain what is hapenning here.

- Marshal the Data into JSON: The data passed to the function is marshaled into a JSON byte array. If there's an error during this process, it returns the error.

jsonBytes, err := json.Marshal(data)

if err != nil {

return err

}

- Prepare the Webhook Request: A new HTTP POST request is created with the JSON data as the body. The "Content-Type" header is set to

application/json.

req, err := http.NewRequest("POST", url, bytes.NewBuffer(jsonBytes))

if err != nil {

return err

}

req.Header.Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

- Send the Webhook Request: An HTTP client sends the prepared request. If there's an error sending the request, it returns the error. The response body is also deferred to close after processing.

client := &http.Client{}

resp, err := client.Do(req)

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer func(Body io.ReadCloser) {

if err := Body.Close(); err != nil {

log.Println("Error closing response body:", err)

}

}(resp.Body)

- Determine the Status Based on the Response Code: The status of the webhook is determined based on the HTTP response code. If the status code is

200 (OK), the status is set to "delivered"; otherwise, it's set to "failed", then an error is returned with the status code.

...

status := "failed"

if resp.StatusCode == http.StatusOK {

status = "delivered"

}

log.Println(status)

if status == "failed" {

return errors.New(status)

}

...

- Return Success: If everything is successful, the function returns

nil, indicating that the webhook was sent successfully.

This is the logic for sending the request. Nothing yet complicated yet, but we are getting into the juiciest parts 🤫. Let's add the package to handle listening to the payments Redis channel.

Listening to the Redis channel

Another important aspect of the webhook service is that it should be actively listening to the payments Redis channel. It is the concept of the pub/sub feature of Redis. The Flask service publishes data into a channel, then all services subscribed to this channel receive the data.

In the root of the webhook directory project, create a new directory called redis. Inside this directory created a new file called redis.go. This file will contain the logic that will subscribe and listen to incoming data in the payments channel but also format the payload, and send it to a Golang queue channel.

package redis

import (

"context"

"encoding/json"

"log"

"github.com/go-redis/redis/v8"

)

// WebhookPayload defines the structure of the data expected

// to be received from Redis, including URL, Webhook ID, and relevant data.

type WebhookPayload struct {

Url string `json:"url"`

WebhookId string `json:"webhookId"`

Data struct {

Id string `json:"id"`

Payment string `json:"payment"`

Event string `json:"event"`

Date string `json:"created"`

} `json:"data"`

}

Let's write the Subscribe function.

func Subscribe(ctx context.Context, client *redis.Client, webhookQueue chan WebhookPayload) error {

// Subscribe to the "webhooks" channel in Redis

pubSub := client.Subscribe(ctx, "payments")

// Ensure that the PubSub connection is closed when the function exits

defer func(pubSub *redis.PubSub) {

if err := pubSub.Close(); err != nil {

log.Println("Error closing PubSub:", err)

}

}(pubSub)

var payload WebhookPayload

// Infinite loop to continuously receive messages from the "webhooks" channel

for {

// Receive a message from the channel

msg, err := pubSub.ReceiveMessage(ctx)

if err != nil {

return err // Return the error if there's an issue receiving the message

}

// Unmarshal the JSON payload into the WebhookPayload structure

err = json.Unmarshal([]byte(msg.Payload), &payload)

if err != nil {

log.Println("Error unmarshalling payload:", err)

continue // Continue with the next message if there's an error unmarshalling

}

webhookQueue <- payload // Sending the payload to the channel

}

}

This code defines a function called Subscribe, which subscribes to a specific Redis channel ("payments") and continuously listens for messages on that channel. When a message is received, it processes the message and sends it to a Go channel for further handling.

- The code subscribes to the "payments" channel in Redis using the provided Redis client. Any messages sent to this channel will be received by this function.

pubSub := client.Subscribe(ctx, "payments")

- Then, we ensure that the PubSub (publish-subscribe) connection to Redis is closed when the function exits, whether it ends normally or due to an error. This is important for cleaning up resources.

defer func(pubSub *redis.PubSub) {

if err := pubSub.Close(); err != nil {

log.Println("Error closing PubSub:", err)

}

}(pubSub)

- The

forloop here runs indefinitely, allowing the function to keep listening for messages as long as the program is running.

for {

// ...

}

Inside the loop, the code waits to receive a message from the Redis channel. If there's an error receiving the message, mostly in the deserialization of the payload, the function logs the error and we continue the execution of the function.

err = json.Unmarshal([]byte(msg.Payload), &payload)

if err != nil {

log.Println("Error unmarshalling payload:", err)

continue // Continue with the next message if there's an error unmarshalling

}

Once a message is received, the code attempts to convert the message payload from JSON into a Go structure (WebhookPayload). If there's an error in this process, it logs the error and continues to the next message.

- Finally, the code sends the processed payload to a Go channel (

webhookQueue). This channel will be used in thequeuepackage to handle the payload.

webhookQueue <- payload // Sending the payload to the channel

To put it simply, this function acts like a radio receiver tuned to a specific station (payments channel in Redis). It continuously listens for messages (like songs on the radio) and processes them (like adjusting the sound quality), then passes them along to another part of the program (like speakers playing the music). (Okay! I am trying my best with these weird analogies!😤)

Now that we have the Subscribe method, let's add the queuing logic. This is where we will implement the retry logic.

Adding the queuing logic

A queue is a data structure that follows the First-In-First-Out (FIFO) principle. Think of it like a line of people waiting at a bank; the first person in line gets served first, and new people join the line at the end.

In Golang, you can work with queues in two principal ways:

Slices: Slices are dynamically-sized arrays in Go. You can use them to create simple queues by adding items to the end and removing them from the beginning.

Channels: Channels are more complex but offer greater possibilities. They allow two goroutines (concurrent functions) to communicate and synchronize their execution. You can use a channel as a queue, where one goroutine sends data into the channel (enqueue), and another receives data from it (dequeue).

In our specific case, we'll use channel-based queuing. Here's why:

Concurrency: Channels are designed to handle concurrent operations, making them suitable for scenarios where multiple functions need to communicate or synchronize.

Capacity Control: You can set a capacity for a channel, controlling how many items it can hold at once. This helps in managing resources and flow control.

Blocking and Non-Blocking Operations: Channels can be used in both blocking and non-blocking ways, giving you control over how sending and receiving operations behave.

We'll use a channel to send data from the Subscribe function and then process this data in the ProcessWebhooks function, which we'll write next. By using channels, we ensure smooth communication between different parts of our program, allowing us to handle webhooks efficiently and reliably.

Writing the queuing logic

At the root of the webhook project, create a directory called queue. Inside this directory, add a file called worker.go. This file will contain the logic to process the data received in the queue.

mkdir queue && cd queue

touch worker.go

As usual, let's first start with the imports.

package queue

import (

"context"

"log"

"time"

"webhook/sender"

redisClient "webhook/redis"

)

And then add the function to process the webhooks data, ProcessWebhooks.

func ProcessWebhooks(ctx context.Context, webhookQueue chan redisClient.WebhookPayload) {

for payload := range webhookQueue {

go func(p redisClient.WebhookPayload) {

backoffTime := time.Second // starting backoff time

maxBackoffTime := time.Hour // maximum backoff time

retries := 0

maxRetries := 5

for {

err := sender.SendWebhook(p.Data, p.Url, p.WebhookId)

if err == nil {

break

}

log.Println("Error sending webhook:", err)

retries++

if retries >= maxRetries {

log.Println("Max retries reached. Giving up on webhook:", p.WebhookId)

break

}

time.Sleep(backoffTime)

// Double the backoff time for the next iteration, capped at the max

backoffTime *= 2

log.Println(backoffTime)

if backoffTime > maxBackoffTime {

backoffTime = maxBackoffTime

}

}

}(payload)

}

}

Let's understand the code above. The function called ProcessWebhooks takes a Go channel containing webhook payloads and processes them. If sending a webhook fails, it retries using an exponential backoff strategy.

- First, we loop through the list of items in the

webhookQueuechannel. As long there will be items in the list, we will keep processing the data.

for payload := range webhookQueue {

// processing code

}

- For each payload, a new goroutine (a lightweight thread) is started. This allows multiple webhooks to be processed simultaneously.

go func(p redisClient.WebhookPayload) {

- Next, we initialize the variables to control the retry logic. If sending a webhook fails, the code will wait (

backoffTime) before trying again. This wait time doubles after each failure, up to a maximum (maxBackoffTime). The process will be retried up tomaxRetriestimes.

backoffTime := time.Second // starting backoff time

maxBackoffTime := time.Hour // maximum backoff time

retries := 0

maxRetries := 5

- In the next part, we attempt to send the webhook using the

SendWebhookfunction. If it succeeds (err == nil), the loop breaks and the process moves to the next payload.

err := sender.SendWebhook(p.Data, p.Url, p.WebhookId)

if err == nil {

break

}

log.Println("Error sending webhook:", err)

- If sending the webhook fails, the code logs the error, increments the retry count, and waits for the

backoffTimebefore trying again. The backoff time doubles with each failure but is capped atmaxBackoffTime.

retries++

if retries >= maxRetries {

log.Println("Max retries reached. Giving up on webhook:", p.WebhookId)

break

}

time.Sleep(backoffTime)

backoffTime *= 2

if backoffTime > maxBackoffTime {

backoffTime = maxBackoffTime

}

The ProcessWebhooks function is designed to process a queue of webhook payloads. It attempts to send each webhook, and if it fails, it retries using an exponential backoff strategy. By using goroutines, it can handle multiple webhooks concurrently, making the process more efficient.

In simple terms, this function is like a post office worker trying to deliver packages (webhooks). If a delivery fails, the worker waits a bit longer each time before trying again, up to a certain number of tries. If all attempts fail, the worker moves on to the next package.

We have written the most important parts of the service. Let's put all of them together.

Putting everything together

It is time to put everything we have written together. Inside the main.go file, we will add the logic to create a Redis client to start the connection, create the channel that will act as the queue, and then start the required processes.

package main

import (

"context"

"log"

"os"

redisClient "webhook/redis"

"webhook/queue"

"github.com/go-redis/redis/v8" // Make sure to use the correct version

)

func main() {

// Create a context

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel()

// Initialize the Redis client

client := redis.NewClient(&redis.Options{

Addr: os.Getenv("REDIS_ADDRESS"), // Use an environment variable to set the address

Password: "", // No password

DB: 0, // Default DB

})

// Create a channel to act as the queue

webhookQueue := make(chan redisClient.WebhookPayload, 100) // Buffer size 100

go queue.ProcessWebhooks(ctx, webhookQueue)

// Subscribe to the "transactions" channel

err := redisClient.Subscribe(ctx, client, webhookQueue)

if err != nil {

log.Println("Error:", err)

}

select {}

}

Let's explain the code above.

- We first start with the package declaration and the imports

package main

import (

"context"

"log"

"os"

redisClient "webhook/redis"

"webhook/queue"

"github.com/go-redis/redis/v8" // Make sure to use the correct version

)

Then, we declare the main function that will first create a context.

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel()

A context is created to manage cancellation signals across different parts of the program. This is useful for gracefully shutting down processes if needed.

- We then initialize the Redis client by creating a connection to the Redis server using the address in the environment variable.

client := redis.NewClient(&redis.Options{

Addr: os.Getenv("REDIS_ADDRESS"), // Use an environment variable to set the address

Password: "", // No password

DB: 0, // Default DB

})

- The next parts are absolutely important because we first start by creating a channel that will act as a queue for the webhook payloads.

webhookQueue := make(chan redisClient.WebhookPayload, 100) // Buffer size 100

go queue.ProcessWebhooks(ctx, webhookQueue)

It has a buffer size of 100, meaning it can hold up to 100 items at once. We start a goroutine to process webhooks from the webhookQueue channel. The processing logic is defined in the ProcessWebhooks function.

- Then, we subscribe to a Redis channel called

paymentsand listen for messages. When a message is received, it's added to thewebhookQueuechannel for processing.

err := redisClient.Subscribe(ctx, client, webhookQueue)

if err != nil {

log.Println("Error:", err)

}

Then at the end of the function, we create an infinite loop that keeps the program running.

select {}

Without this, the program would exit immediately after starting the goroutines, and they wouldn't have a chance to run.

To put it simply, this code sets up a simple webhook processing system using Redis. It initializes a connection to Redis, creates a channel to act as a queue, starts a goroutine to process webhooks, and subscribes to a Redis channel to receive new webhook payloads. The program then enters an infinite loop, allowing the goroutines to continue running and processing webhooks as they arrive.

Now that we have all the files required for the webhook service to work. We can dockerize the application and start the docker containers.

Running the project

It is time to run the project. Let's add a Dockerfile and the needed environment variables. In the webhook go project, add the following Dockerfile.

# Start from a Debian-based Golang official image

FROM golang:1.21-alpine as builder

# Set the working directory inside the container

WORKDIR /app

# Copy the go mod and sum files

COPY go.mod go.sum ./

# Download all dependencies

RUN go mod download

# Copy the source code from your host to your image filesystem.

COPY . .

# Build the Go app

RUN CGO_ENABLED=0 GOOS=linux go build -a -installsuffix cgo -o main .

# Use a minimal alpine image for the final stage

FROM alpine:latest

# Set the working directory inside the container

WORKDIR /root/

# Copy the binary from the builder stage

COPY --from=builder /app/main .

# Run the binary

CMD ["./main"]

With the Dockerfile written we can now start the docker containers, but first, you need to have a webhook URL to try this project. You can easily get a free one at webhook.site. Once it is done, create a file called .env at the root of the project, where the docker-compose.yaml file is present. Then, make sure to have similar content.

REDIS_ADDRESS=redis:6379

WEBHOOK_ADDRESS=<WEBHOOK_ADDRESS>

Replace <WEBHOOK_ADDRESS> with the webhook URL provided by webhook.site.

Then, build and start the container with docker compose up -d --build.

Once the build is finished, you can use the docker compose logs -f command to track the logs of the webhook service.

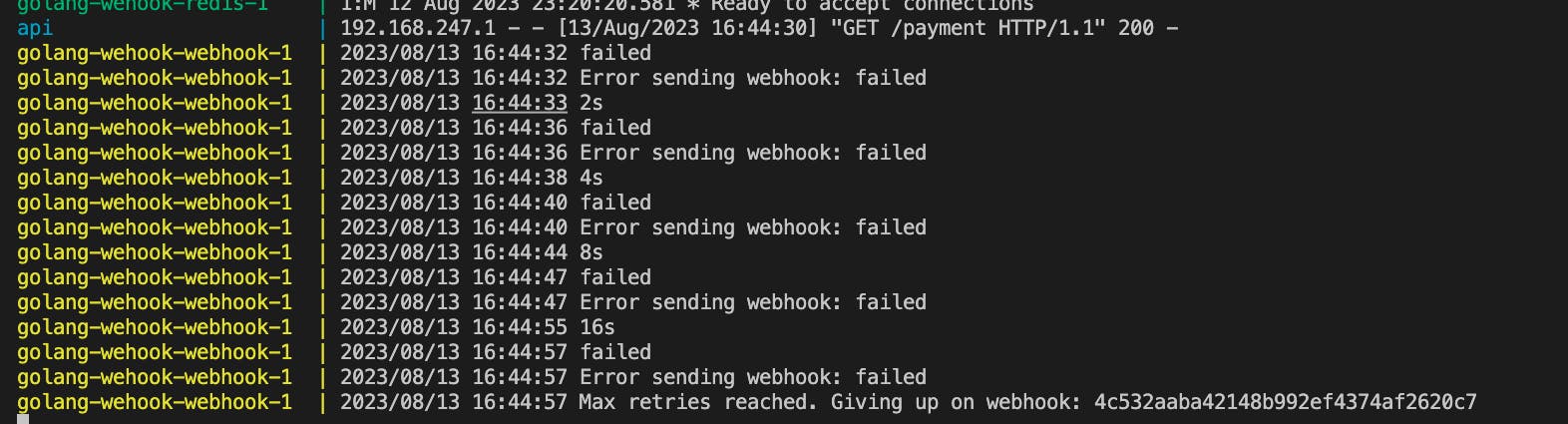

Hit 127.0.0.1:8000/payment to start sending data to the webhook service through Redis. In case of errors, here is what the logs will look like.

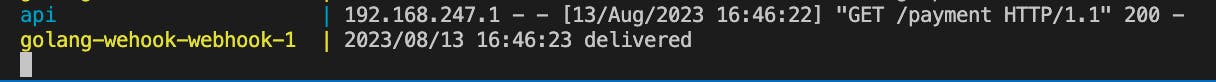

And the logs in case of success.

Note: To tweak the behaviors of the webhook to receive errors, you can modify the status sent upon receiving the request. On the

webhook.sitedashboard, click on theEditbutton on the navigation bar. Then change theDefault status codeto504to indicate a server timeout.

Congratulations! We have just built a webhook service in Golang. We have explored the Redis channel, queuing using channels in Golang but also exponential backoff and goroutines.🔥

Let's quickly discuss some ameliorations to the solution we have implemented.

What we can do better?

While the solution we've implemented is functional and demonstrates key concepts like concurrent processing, exponential backoff, and Redis integration, there are several areas where it can be improved. Here's a breakdown of some of the pitfalls and how we can address them:

Scalability

The current implementation of our webhook service leverages Redis, queuing, and goroutines. While this is a solid foundation, it may not be sufficient for handling a large number of concurrent webhooks.

Goroutines, although lightweight, consume system resources. An overwhelming number of concurrent webhooks could exhaust these resources, leading to slow processing or even system failure. Additionally, Redis, despite its speed, can become a bottleneck if the number of read/write operations exceeds its capacity, resulting in delays.

A single point of failure also exists in our system. If the Redis server goes down, the entire system can become inoperable, leading to loss of data and service disruption.

To address these scalability challenges, we can consider the following enhancements:

Implementing a Distributed Queue System: Systems like Kafka or RabbitMQ can handle a larger number of messages and distribute the load across multiple servers.

Utilizing Worker Pools: Managing goroutines with worker pools can control resource usage and prevent system overload.

Horizontal Scaling: By adding more instances of the webhook service and using a load balancer, we can distribute the load evenly and handle more requests.

Security

Security is another critical aspect that requires attention. Currently, our Redis server does not use a password, leaving it vulnerable to unauthorized access. Anyone who can connect to the Redis server can read or write data, posing a risk of potential data breaches.

Furthermore, if the Redis server goes down, the system may lose the payloads sent, leading to data loss. To mitigate this risk, we can:

Use a Redis Password: This simple measure can prevent unauthorized access to the Redis server.

Set Up Replication: Redis replication ensures that there's a copy of the data on another server, providing a fallback if one server goes down.

Enable Persistence: Regularly saving data to disk ensures that data can be recovered if the server crashes.

If the webhook server itself is down, payloads will not be processed, and data may be lost. To address this, we can:

Implement a Retry Mechanism: A robust retry mechanism with exponential backoff ensures continued attempts to process the payload.

Monitor and Alert: Monitoring and alerting can notify administrators of server downtime, enabling quick intervention.

Utilize Backup Servers: Having backup or failover servers ensures continuous service if one server goes down.

Conclusion

The webhook service you've built is a solid foundation, and these enhancements can take it to the next level. By focusing on scalability, reliability, security, and maintainability, you can build a system that not only meets the current requirements but is also prepared for future growth and changes. Always consider the specific needs and constraints of your application, as not all improvements may be necessary or applicable to your particular use case.

If you think that this article could have been made better, feel free to comment below.

Also, you can check the code source of the project of this article on GitHub.